|

|

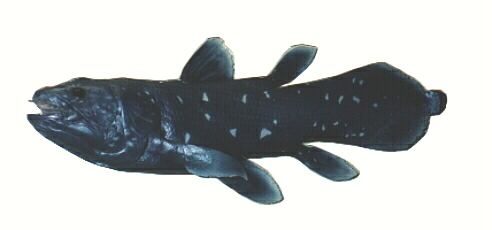

In December 1938, an incredible fish was brought in at the docks of East London, South

Africa. It was a lobe finned fish which possessed primitive limbs instead of typical fins. This coelacanth (pronounced SEE-la-kanth),

Latimeria chalumnae, signified one of the greatest scientific finds of the 20th century. It also signified the beginning of

a steady decline in coelacanth population at the hands of science.

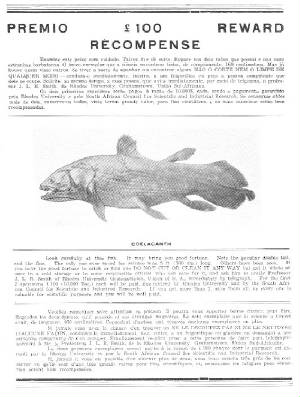

The great excitement resulting from this original

discovery led to an intense search for additional specimens. The initial rewards offered were one of the first serious threats

to the original population, which was found along the Comoros Islands. In the ensuing years, scientific institutions worldwide

clamored for their very own specimens to study and display. Comoros Islanders were encouraged to catch coelacanths to fill

requests from these scientific institutions. Without doubt, much important information has been learned from many of these

studies. However, the population suffered tremendously as a result.

The Holy Grail for any institution would be the

public display of a living coelacanth. There has been past desire among institutions, particularly in Japan and the United

States, to capture such a coelacanth. To date, it's unlikely that any coelacanth has survived the stresses of being caught

and brought to the surface. Attempts to capture a live specimen would surely result in additional coelacanth mortality.

New

populations discovered off of South Africa, Indonesia, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, and most recently Tanzania

may lead to further discoveries, as well as the danger of a severe decline similar to that seen off the Comores.

Hopefully, steps will quickly be implemented to prevent the repeat of past mistakes. Additionally, the knowledge that there

are now "new populations" may lead to a further reduction in conservation efforts based on a false impression that they are

now plentiful. DNA reports indicate that the Indonesian population is a new species of coelacanth. This Indonesian population

has been given the scientific name Latimeria menadoensis.

Of course, Latimeria was not really "discovered." The local

fishing inhabitants of both Sulawesi, Indonesia and the Comoros Islands were well aware of the species long before the scientific

community got involved. Fishermen in both locations even had preexisting names for the fish. The Comoros Islanders refer to

Latimeria as gombessa. In north Sulawesi, they are know by the name raja laut, or "king of the sea."

The coelacanth

has managed to survive relatively unchanged for nearly 400 million years. Though originally thought to be extinct for more

than 60 million years, it wasn't until their rediscovery in the twentieth century that they faced their greatest challenge

for survival.

The majority of preservation attempts to date can only be characterized as "Band-Aid Conservation,"

resulting in mostly disappointing results. Beyond scientific circles, coelacanth awareness is woefully inadequate.

The political climates and finances of the governments adjacent to the populations are an obstacle as well. The United Nations

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) has barred all international trade regarding this severely

endangered species. The coelacanth is also listed under the United States Endangered Species Act (ESA) for foreign species.

There are restrictions on harming or killing the species for parties subject to United States jurisdiction, and the listing

increases recognition of the species' plight while promoting conservation efforts. However, human predation continues to

be a serious problem. Perhaps as few as 500 individuals still survive along the Comores today.

Of great concern is an increase in trawling by Japanese fishing boats and others in areas where coelacanths live.

The governments of South Africa, Indonesia, Tanzania, and the Comoros Islands are all in the process of trying to limit

fishing in their respective coelacanth habitats.

Coelacanth preservation efforts must go far beyond current efforts, before it is too late. It's time for scientific unity

in regard to the coelacanth. Scientific institutions must come to a joint consensus regarding the preservation of this species

as soon as possible. Lack of action will simply be a continuation of the past mistakes made by the scientific community.

It is my hope that additional populations of Latimeria currently exist in the secluded

spaces of the Indian, and perhaps even Pacific Oceans. It is also my hope that these possible populations will for now remain

undiscovered by the species which may ultimately lead to their extinction--man.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phulum: Chordata

Class: Sarcoptergii

Order: Coelacanthiformes

Family: Latimeriidae

Genus: Latimeria

Species: Chalumnae (Comoros)

Species: Menadoensis (Indonesia)

|

| JLB Smith coelacanth leaflet--Click to enlarge |

|

| Marjorie Courtney-Latimer and Latimeria chalumnae |

| X-ray from Smithsonian Museum of Natural History |

|

| Click to enlarge |

Click here for the very latest in Coelacanth News

Recommended coelacanth reading:

Fossil

Fish Found Alive; Discovering the Coelacanth

Sally M. Walker

Carolrhoda Books 2002

A Fish Caught In Time

Samantha

Weinberg

HarperCollins 2000

Living Fossil; The Story of the Coelacanth

Keith S. Thomson

W.W. Norton &

Co. 1991

Search For a Living Fossil; The Story of the Coelacanth

Eleanor Clymer

Holt Reinhart Winston 1963

(youth)

Old Fourlegs; The Coelacanth

J.L.B. Smith

Longmans 1956

The Search Beneath the Sea

J.L.B.

Smith

Holt & Co. 1956 (USA version)

|

|

|